The Rio Grande Valley is uniquely defined by diverse bodies of water. On our eastern coastline is the Gulf of Mexico, an ocean basin shared by Brownsville, Cancun, Havana and Miami. The Rio Grande is the southern border of our four-county region as well as the international border between the U.S. and Mexico. Scattered underneath our soil is a series of underground “norias,” or artesian wells, which were accessed by early Indigenous tribes and Spanish colonists in our semi-arid environment.

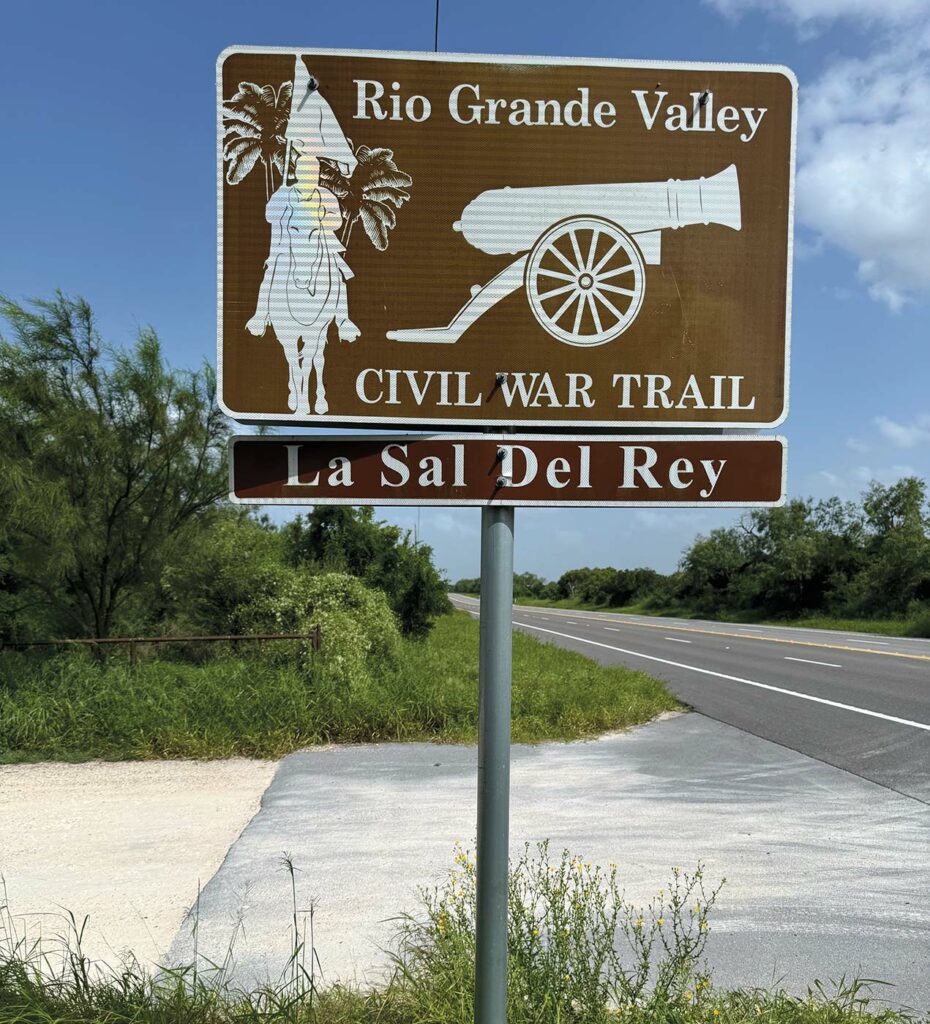

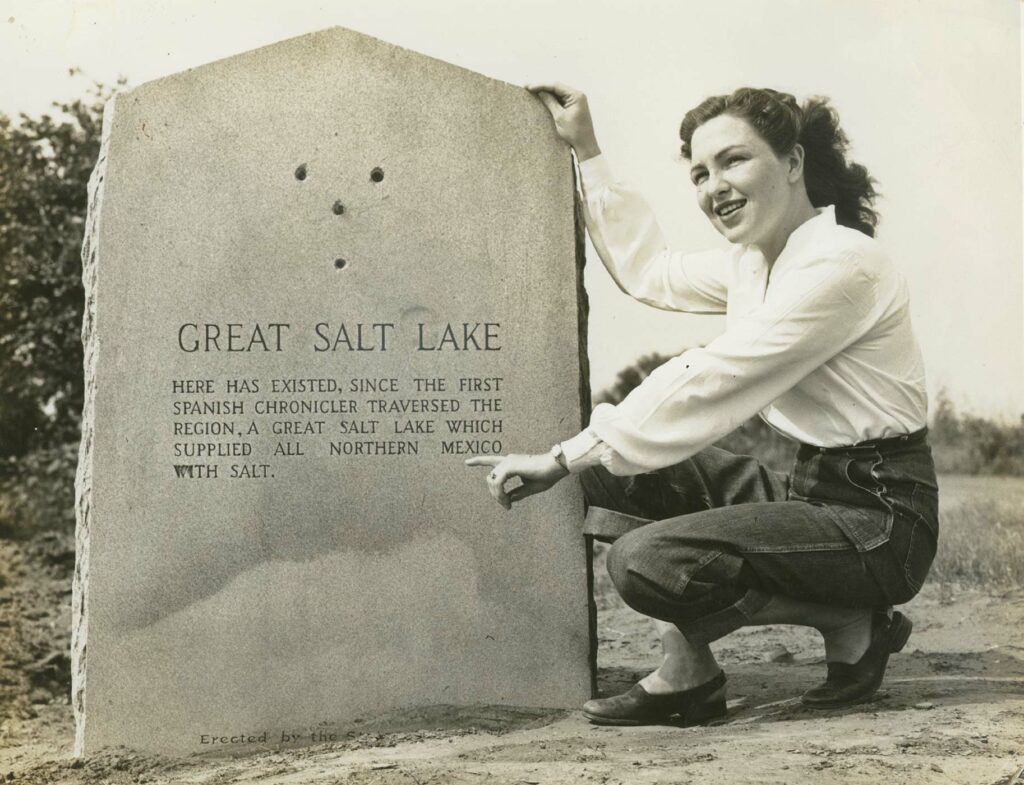

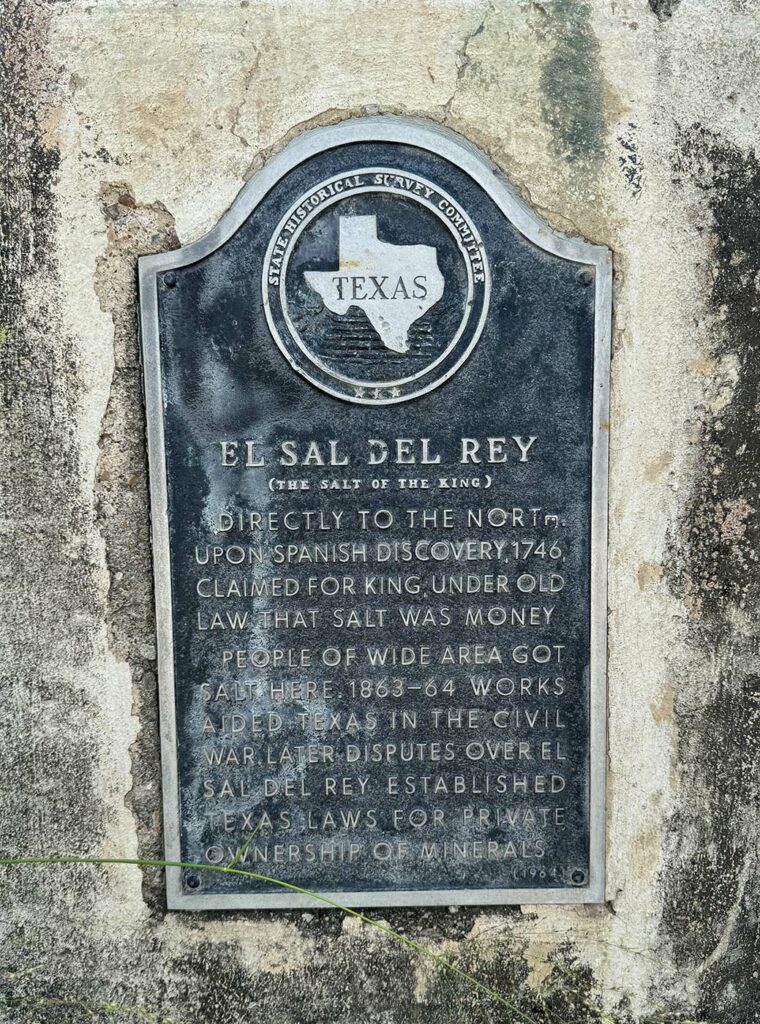

We even have a natural salt lake north of Edinburg, near the cattle ranching community of San Manuel. Known as La Sal del Rey or “the salt of the king,” this lake was a hub for ancient tribal activity and played an important role in Spanish colonial history.

When I was a young passenger in the family station wagon, I remember seeing the salt lake shimmering beyond the heavy green brush as we drove towards Raymondville. In those days, La Sal del Rey was on private property. Nowadays, the lake is part of the Lower Rio Grande Valley National Wildlife Refuge. It’s a favorite hiking spot for my kids and their friends. This salt lake never fails to amaze visitors in its size, a mile long and five miles around. Most of the comments I have heard over the years have been, “Gee, I didn’t even know this was here.”

“This salt lake never fails to amaze visitors in its size. Most of the comments I have heard over the years have been, ‘Gee, I didn’t even know this was here.’”

These days, the salt lake is quiet, with the exception of families and day trippers who hike 30 minutes down a mesquite- and cactus-lined path to see this natural phenomenon. But 300 years ago, La Sal del Rey and its sister La Sal Vieja (“the old salt lake”) were highly significant natural resources in Rio Grande Valley.

We don’t know what the salt lakes were named before Spanish colonists arrived, but we know they were important. Water levels in the lakes rise and fall, leaving crystalized crusts of salt to dry in the sun. Once collected, the natural salt can be used to preserve meats and process animals hides into leather.

Aside from salt’s value as a preservative and processing chemical, the lake itself still attracts white-tailed deer, racoons, opossums and javalinas as a salt lick, making the area around the salt lake a densely populated wildlife habitat. Archeological evidence, such as arrowheads and stone tools, shows that tribes camped at the salt lakes. Fresh meat from a successful hunting expedition could have been salted, dried in the hot sun and preserved on the spot.

But how could a salt lake located in Texas be claimed by a Spanish king over 5,000 miles away? In the year 1492, when King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella agreed to pay for Columbus’ journey to the New World, the understanding was that the royal couple would receive a return on their investment. They believed Columbus would find gold, silver, pearls and jewels.

However, unlike the gold nuggets and silver bars that we see in the movies, most gold and silver deposits exist in ore, a natural rock that contains various types of minerals and occasionally precious metals. The extraction process for separating the silver or gold from the ore required salt. Without salt, there was no gold or silver to send back to Spain.

In order for Ferdinand, Isabella and their royal Spanish successive heirs to get their gold and silver, their royal agents in the New World first needed to claim any and all salt supplies.

If you are interested in a deeper historical dive on how the King of Spain could legally claim the salt in New Spain (aka Texas,) research the life of Francisco Xavier de Gamboa, an attorney who published Comentarios a las Ordenanzas de Minas (Comments on Mining Ordinances) in 1761. In his commentary, Gamboa defended the existing framework based on the Royal Mining Ordinances of 1584 including the assumption that the Spanish government owned all the subsurface minerals in Spanish territory (aka New Spain, aka Texas.) Private property owners’ rights were secondary to the royal ownership of undiscovered treasures hidden below the dirt.

Texas oil and gas law is still based on these early Spanish mineral ownership laws dating back to 1584. When Mexico ceded claims to Texas after the Mexican-American War ended in 1848, all mineral rights, from salt to petroleum, were relinquished to the private property owners.

When you visit the La Sal del Rey, the salt lake will appear quietly on the horizon as you hike the peaceful path to get there. Remember that the Spanish crown’s claim of ownership of the salt there was not just for a culinary ingredient; it was for the untold wealth of the New World.

La Sal del Rey is open year-round. For directions and information, visit the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service website at fws.gov.