Help Create a Sense of Place

Hats off to the lower Rio Grande Valley farmers of a century ago who had the good sense to take advantage of the region’s naturally occurring resacas to irrigate their fields rather than digging canals or laying pipe.

Otherwise, the resaca systems that are such a central feature of the region’s social-cultural-environmental character probably wouldn’t be so central.

Take it from Jude A. Benavides, associate professor of hydrology with the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley’s School of Earth, Environmental, and Marine Sciences. He grew up living on a resaca, still lives on one, has been studying them for more than 20 years and probably knows more about them — particularly the ones that wind their sinewy way through the lower Valley — than anybody.

Those growers of old probably were more concerned with saving money than preserving resacas for future generations, but who cares?

“The fact remains that a lot of the resacas are not as threatened as they could be, because we use them for irrigation purposes,” Benavides says. “And now as irrigation demands decline and urban demands increase, we have another bold decision to make.”

That decision involves how to keep resacas viable for the long haul, but more about that later. Meanwhile, what are they?

“Resaca” is Spanish for “vestige” (also “hangover”). There is no shortage of misconceptions. They are not, for instance, exclusively oxbow lakes, formed when a river bypasses out a bend to carve out a more direct course, but they do include oxbow lakes, Benavides says.

They are also abandoned distributaries (not tributaries), secondary river channels and old meanders — characterized by a “curvy, bendy path, like a snake,” according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

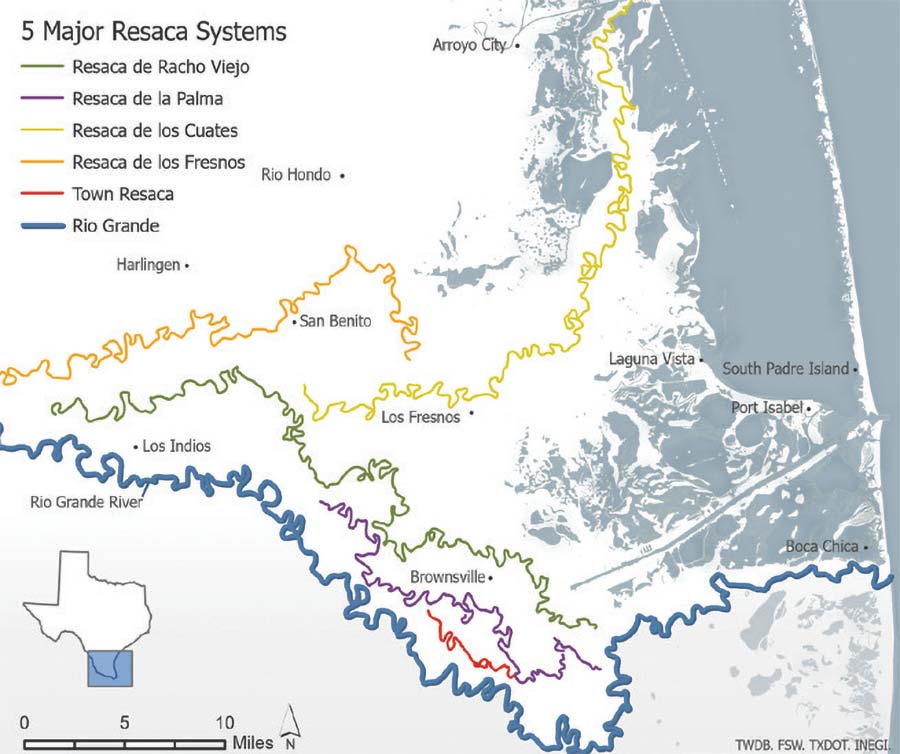

“They encompass abandoned waterways of the Rio Grande over the course of the last several thousand years,” Benavides says. “The whole network encompasses a good one-third of the southeastern Valley and a good section of northeastern Tamaulipas.”

The Valley’s five major resaca systems are, from north to south, Resaca de los Fresnos, Resaca de los Cuates, Resaca del Rancho Viejo, Resaca de la Palma and Town Resaca, which squiggles through the heart of Brownsville, including Dean Porter Park and Gladys Porter Zoo, skirting Old City Cemetery.

Generations of South Texans have grown up, courted and picnicked alongside them, fished them, swam them (not recommended), and thrown old tires and other junk in them (bad idea). Resacas figure in the area’s history, culture and stories, they beautify the landscape and they support copious wildlife — most conspicuously a breathtaking assortment of birds.

“It imbues the area with a sense of place, particularly for those that grew up in and around them,” says Benavides, who lives on Resaca de la Palma.

The Brownsville Public Utilities Board (BPUB) and the city of Brownsville jointly manage most of Town Resaca, which is a major storm water collector and kept flowing with raw water from the Rio Grande, a good reason for not swimming in it, Benavides says. You can of course paddle your canoe, kayak or pirogue on it and the other resacas to your heart’s content.

Wet resacas are loaded with fish, from bass to prehistoric alligator gar, which tends to surprise a lot of people, Benavides says. As far as eating resaca fish, it depends on the particular system. If there’s no flow, then no, he wouldn’t do it, though Benavides has eaten bass on occasion pulled out of Resaca de los Cuates. That said, he’d avoid gar. They live a long time and accumulate too much bad stuff in their bodies, Benavides says.

One of his neighbors is Traci Wickett, who retired last year as head of the United Way of Southern Cameron County and lives with her husband, Rick, on Resaca de la Palma. Like Benavides, she loves resaca life — especially along her particular stretch. What used to be farmland on the opposite bank from the Wicketts’ property was acquired years ago by Texas Parks & Wildlife, reforested, and will never be developed.

“The land across the resaca from us will be forever wild,” Traci Wickett says. “There’s just wildlife galore across the resaca from us that comes and visits our feeders, our yard, our dock. It’s just magical. We love hearing the coyotes howling, and the chachalacas have a big time over there. We’ve seen a bobcat come down and drink from the resaca.”

Wickett can watch the sunrise from her backyard, and loves the way the moon and clouds are reflected in the water. Don’t forget the birds: green jays, whistling ducks, pelicans, herons and egrets, to name a few.

“We’ve got feeders out right now for the orioles,” she says. “One of them comes around squawking at me like, ‘Come on, where’s my jelly?’”

BPUB is 10 years into a vast resaca-restoration project for the pieces it manages. It involves dredging, removing invasive vegetation and planting native vegetation and other improvements. Funding comes from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the RESTORE Act, though most of the activity now is associated with RESTORE while BPUB waits for USACE funding to restart. Town Resaca, through the zoo, the park and the old cemetery, has already been dredged and other improvements made.

Ryan Greenfeld, BPUB’s communications and public relations manager, said preliminary engineering work and all the design work have been completed for Resaca de la Palma at Brownsville’s old Jagou Plantation site (founded in 1872 by French immigrant Celestine Jagou). Now they’re waiting on USACE funding, which depends on the whims of Congress.

“The project does have a new status,” Greenfeld says. “It has been listed as a Corps project. There are lots of really big obstacles that you have to overcome before you can get any funding. Right now we’re keeping an eye on (Washington) D.C. to see where things go.”

Meanwhile, BPUB, using RESTORE funds, is dredging bits of Town Resaca, replacing native vegetation and doing bank improvements, he says. Crews were taking samples from the Prax Orive Jr. (Sunrise) Park in Brownsville to gauge the amount of sediment.

“Aside from just taking samples they’re also going in and physically probing, going out on a boat and feeling around to get an idea of what’s in there,” Greenfeld says. Tree stumps, for instance, or tires.

When crews dredged Old City Cemetery they kept having to stop to remove tires, shopping carts and other big junk — much easier said than done. BPUB would like to do less of that. But it’s all part of saving the resacas, a massive undertaking with limited funds.

“We have a lot of places we want to do,” Greenfeld says. “We know that there’s a lot of need, but it just takes time and of course funding. It’s something that we’re definitely very committed to, especially when in these last few years we’ve seen a lot of drought.”

The Valley’s sprawling, serpentine, complex resaca systems can’t manage themselves, and without vision, willingness, strategies and money to keep them viable, they’ll eventually cease to exist. Managing them is complicated by the wide range of rainfall variability, between drought and flood, though mostly drought these days.

“They’ll eventually fill up with sediment and go the way of a naturally severed limb,” Benavides says. “But we have an opportunity to squeeze, I’d say, decades if not a couple of hundred years more out of them and potentially more, depending on what we do with water conservation in the Rio Grande watershed.”

Humans have to shoulder the responsibility for sustaining the resacas they enjoy, while scientists like him figure out the best course, Benavides says. At stake is a big chunk of that sense of place.

“They are threatened by a variety of different things,” he adds. “If we don’t take care of them, they will go away. If they go away, the landscape will be changed, unfortunately, forever.”