PHOTOS BY ILIASIS MUNIZ

If you were to stroll the cobbled paseos of French-ruled Mexico City in 1865, you might encounter a strange sight: a flirtatious young gentleman tossing dyed eggshells filled with perfumed powder, slivers of gold paper and trinkets at a fetching señorita, hoping that his overture will garner her favor — or, at least, her attention. No one is certain where the idea of upcycling chicken eggs into a flirtation device originated. That truth vanished in the hazy merengue of centuries. Some accounts trace the peculiar practice to 13th century China and Marco Polo, who allegedly introduced it to Italy, followed by migration to France and Spain.

“Who we are is who we were. Regardless of where the tradition came from, it is a link to past generations and centuries. Cascarones do this.” — Dr. Manuel Medrano, professor emeritus of Mexican-American Heritage and Culture at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley

CUE THE NEW WORLD

What we know is that Empress Carlotta, wife of France’s emperor of Mexico, Maximilian, arrived in 1864, European customs in tow. Some disappeared with his ill-fated reign, although this particular curiosity swept north across the Rio Grande. Now, there’s no denying the popularity of the Valley tradition of cascarones.

In Deep South Texas, cascarones evolved to delight youngsters quite differently. At Easter egg hunts in countless yards, children scramble to fill baskets with confetti eggs while assessing the competition. Sneaking up from behind, they crunch them on unsuspecting victims’ heads, scattering bits of colored paper to the Gulf winds. Some make wishes and hope they come true. Good luck? Perhaps. Messy? Definitely — but oh, so fun.

Dr. Manuel Medrano, professor emeritus of Mexican-American Heritage and Culture at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, considers the longevity of cultural touchstones over centuries.

“Traditions are pliable,” he says, “a confluence of the past and present. What you use in a tradition correlates to how much passion you have for the tradition.” Thousands of eggs expended annually in cascarón-making prove his point.

Today, Becky Taylor McClendon treasures the miniature artworks her mother, Elizabeth White Taylor, painted 60 years ago. She recalls preparing cascarones at home and at Church of the Advent, Episcopal, in Brownsville, before Easter.

“I can still see our kitchen filled with eggshells. We ate dozens of scrambled eggs so Mother would have enough,” says McClendon. “Her eggs came from Tucker’s Egg Farm, across the cotton fields, not far away. Mother would puncture each end and use the contents for baking cakes and pies from scratch. We would wash and dye them pastel colors and set them on racks to dry.”

ENTER THE MAGIC

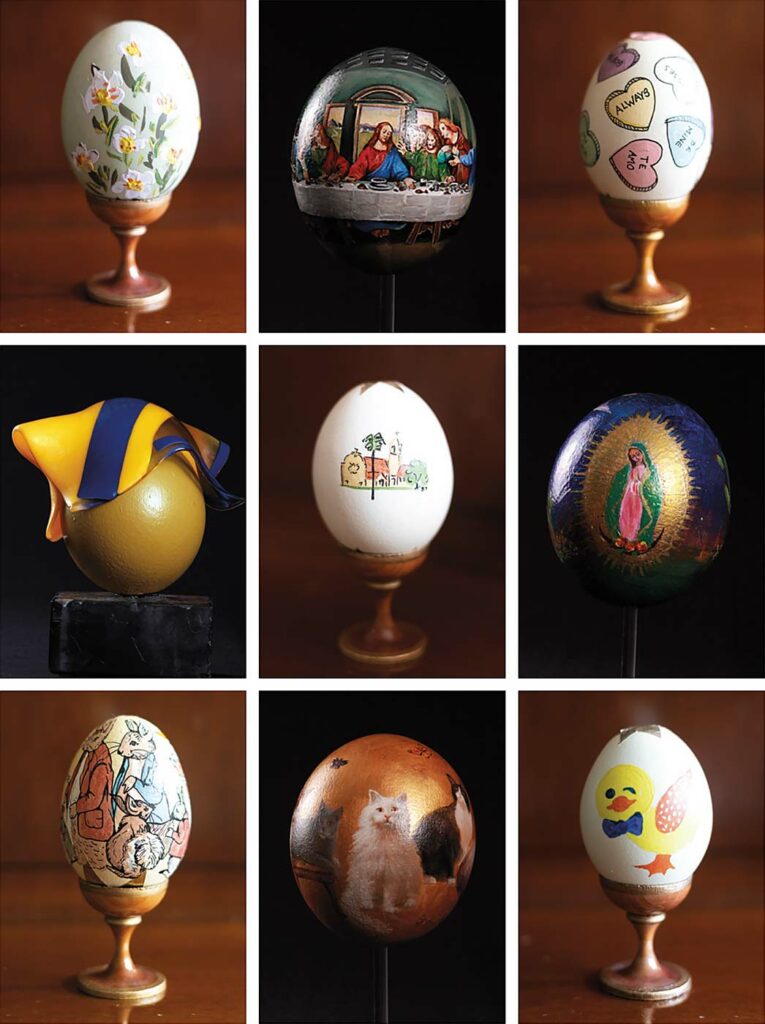

Cascarón makers gather before Holy Week in kitchens, classrooms and fellowship halls, Valleywide. Using spangles, glue and fine brushes, they add love and patience to yield a sum greater than its parts. After sealing the confetti eggs with glue and tissue paper, their alchemy emerges in designs — realistic and fantastic — painted onto the fragile orbs. A frothy seascape, a balding friar, Pogo Possum. Artists sometimes sign their work, hoping it survives. The Church of the Advent’s “egg ladies” still display standouts, as they have for 75 years.

Some eggs never make it to the display case. Too beautiful for child’s play, Viveca Crixell Serafy’s cascarones comprise her private collection. It began in 1983 with an egg her late mother-in-law, Jean Serafy, bestowed in honor of newborn son, Nicholas. “As our family grew, our collection grew,” she says. Nestled in Waterford crystal bowls at Easter, the children knew to look, not touch, and certainly never to break.

One twist on decorating eggs, loosely based on cascarones, uses a grander canvas — ostrich eggs. In 1985, Easterseals RGV in McAllen hatched a plan to paint and sell a clutch of these mammoth eggs as a fundraiser. The idea took flight.

“Word got around until, now, it’s tradition,” says Executive Director Pattie Rosenlund. Proceeds support early childhood and disability programming. “Artists like Luis Sottil, Sister Norma Pimentel, Berry Fritz and Dania Olivares are highly sought after by collectors.” With Lilliputian precision, they depict a lazuli bunting in eyepopping plumage, Our Lady of Guadalupe, New York’s Chrysler Building, The Last Supper. Over a dozen eggs hit the auction floor each fall, gaveling up to $10,000. The coveted Carats’ “Mystery Egg” requires the winner to crack it, liberating jewelry within.

Some might ask why, in a world besotted with fast fashion and flash fiction, anyone would devote time and effort to making something as antiquated as cascarones. Medrano believes their constancy speaks to their significance.

“Who we are is who we were. Regardless of where the tradition came from, it is a link to past generations and centuries. Cascarones do this.”

HOW TO MAKE CASCARONES

What you will need:

- Water, eggs, white vinegar, liquid dyes or food coloring

- Needle, cake rack, baby spoon, paper funnel

- White glue, tissue paper or large foil stars, decorations

With a needle, carefully poke a small hole in the pointed end of an egg. Poke a larger hole in the opposite, rounded end.

Blow through the smaller hole until you force the egg white and yolk out of the larger end.

Repeat the process with as many eggs as you wish to decorate.

Rinse hollowed-out shells. Set on cake rack to dry 1 to 2 days, turning occasionally.

Boil ½ cup of water for each color to be used. Add 1 teaspoon white vinegar per ½ cup.

Into individual small bowls, pour ½ cup of the liquid and add 8 to 10 drops of dye to each.

Use a slotted spoon to dip each egg into the dye. Let sit at least 5 minutes. Remove eggs and allow to dry on rack. Using a baby spoon and paper funnel, fill eggshell with confetti through larger hole.

Cut and glue a small, round piece of tissue paper (or large foil star) to the larger hole to seal it.

Decorate the dry eggs with paint, stickers, Washi tape, glitter or pictures cut out from magazines.

Have fun!