Blasfemus Boasts Texas Agave Spirit

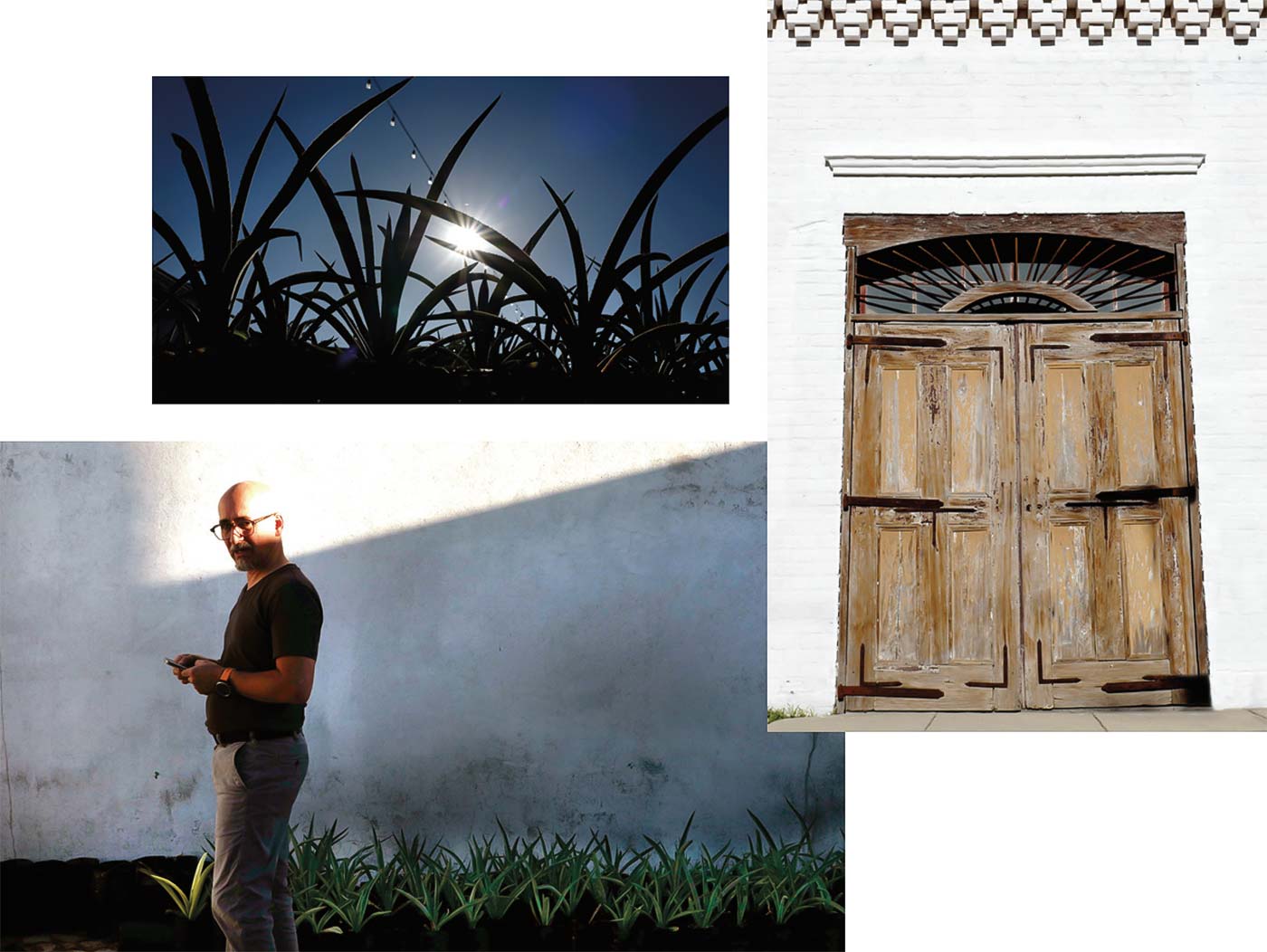

Leonardo Sanchez looks out over a barren clearing in the dense brush alongside the Rio Grande, not far from the border town of Roma, Texas. Two years ago, Sanchez and his partner Eduardo Ocampo Ramirez planted 2,500 spiky agaves on this piece of ground that’s known by the U.S. Border Patrol as a crossing spot for undocumented immigrants and dope smugglers.

Sanchez, co-founder of Ancestral Craft Spirits, envisions one day harvesting the hearts of his Tex-Mex agaves and producing the first Texas-made mezcal. Crops in the hot, arid Rio Grande Valley depend on irrigation; the hardy agave — that stores water in its sharp-tipped leaves — thrives in this climate. Sanchez is counting on the terroir of Starr County to be similar to that of Oaxaca and Jalisco, the chief Mexican states where mezcal and tequila are produced.

But he didn’t predict problems with a pestilential varmint that has overrun Texas. “We came back one day and what we found is that there’s a lot of hogs and javelinas in this area,” he says, with a forced chuckle. “And they like a lot of these little plants. So they ate thousands of them.”

Sales of tequila and mezcal in the U.S. have more than tripled in the last decade, according to the Distilled Spirits Council of the United States, even outselling American whiskey. With that exploding market, Sanchez persevered. He brought more baby agaves from his native Mexico and put them safely in a sunny courtyard next to his distillery. Once he plants them on the riverside acreage — and erects a stout hog-proof fence — it will take at least seven years for the agaves to mature.

“Of course, we will have to take extra measures to protect them,” Sanchez says, “like electric fencing, or maybe we’ll have to pay some men with rifles. I don’t know.” Mexican distillers have been making tequila and its smoky cousin, mezcal, for more than 400 years. Like Champagne from France, if it’s called tequila or mezcal, it has to come from Mexico. If the liquor is produced anywhere else, it is called an agave spirit. Sanchez and Ramirez’s Texas agave spirit is bottled under the brand name Blasfemus.

“Actually there is a story that Eduardo, my partner, was sitting in the board of directors of the Mexican company that makes the mezcal, and he was telling them, ‘We have done some special editions Guerrero, San Luis Potosi. So why don’t we do a special edition Tejas?’ And one of the board members told him that would be blasphemy.”

“‘We have done some special editions Guerrero, San Luis Potosi. So why don’t we do a special edition Tejas?’ And one of the board members told him that would be blasphemy.”

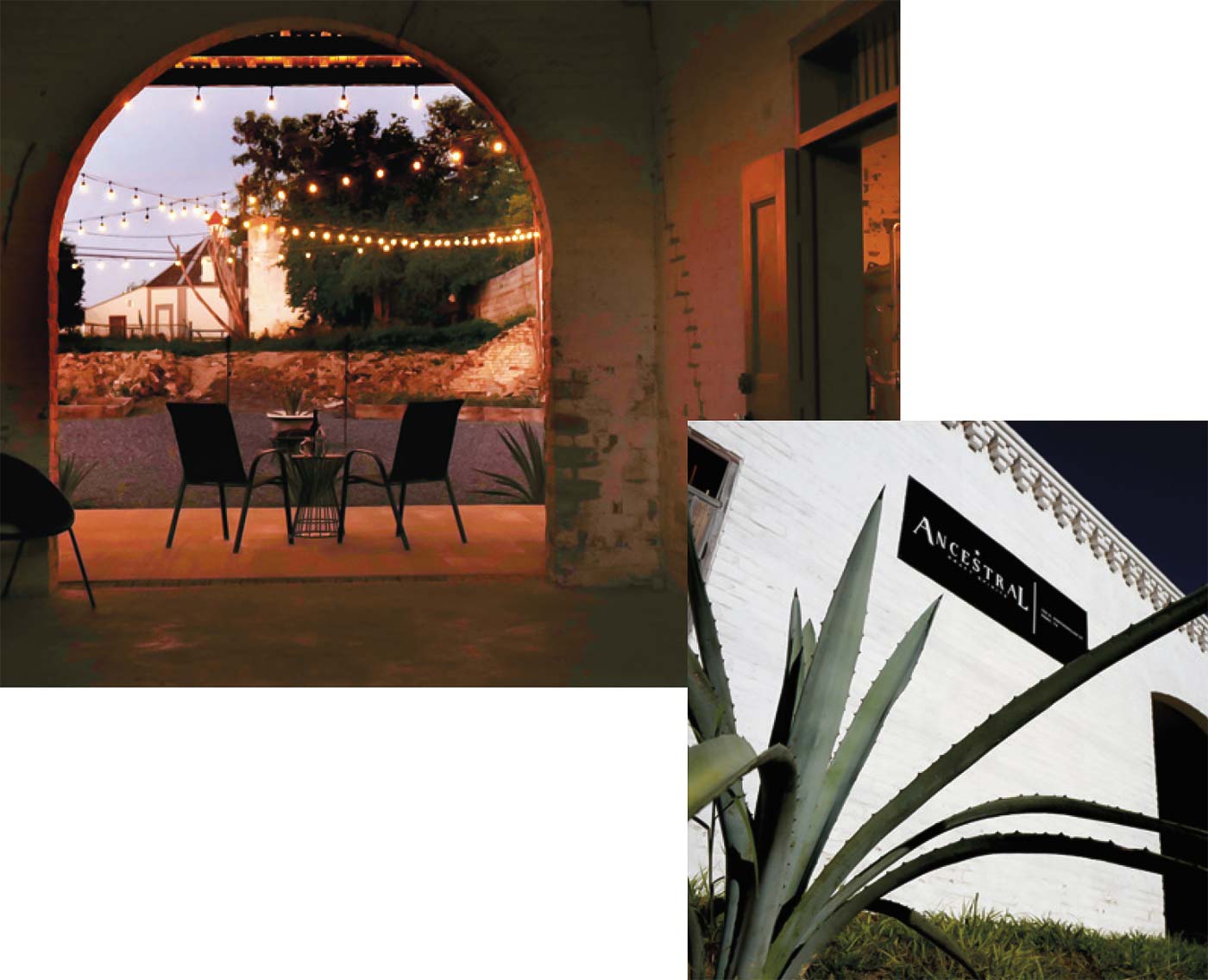

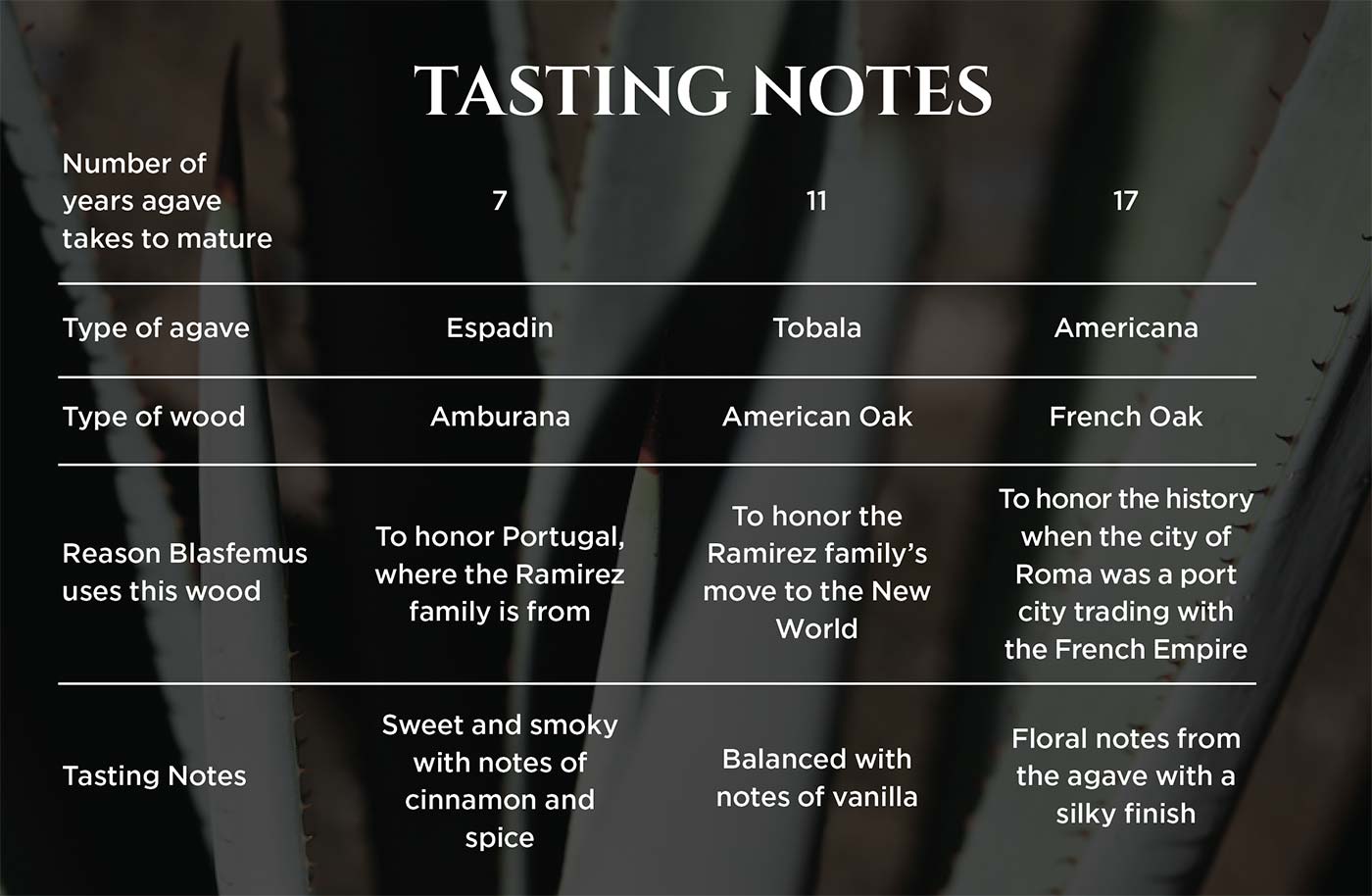

Blasfemus comes in slim black bottles marked with the numerals 7, 11 or 17. But these are not the number of years the liquor has aged in oak barrels, like anejo and reposado tequila. These numbers denote how many years the agave plants have been in the ground. While his agaves are maturing, Sanchez is importing agave juice from his partner’s mezcal estate in Oaxaca. He distills, flavors and bottles it inside a handsome building in historic downtown Roma, formerly the Manuel Guerra General Store, that dates to the mid- 1800s when the town was a steamboat port on the Rio Grande.

The City of Roma — which recently put the image of an agave plant on civic banners hanging downtown — is hoping Ancestral Craft Spirits and its Friday happy hours will help revitalize the moldering historic district on the bluffs overlooking the Rio Grande. As it happens, Roma was not an arbitrary choice for the distillery’s location. Sanchez’s partner, Ramirez, who is involved in the Oaxacan mezcal estate, has longstanding ties to Starr County. His maternal ancestors, the Ramirez family, moved from Portugal in 1739 to a portion of a Spanish land grant north of the Rio Bravo, where the Ramirez home still stands to this day.

Blasfemus is by no means the first American mezcal. California and Hawaii have been growing and distilling agave spirits for nearly a decade. But it is the first made in Texas, and it’s already being poured in cantinas in Houston, Marfa and the Rio Grande Valley.

And how does it compare to traditional Mexican mezcal? “A traditionalist I don’t think would necessarily drink this,” says Chris Galicia, cocktail spirits director of Las Ramblas in Brownsville, after sampling a shot of Blasfemus. Then he quickly adds, “I think things like this are good for a growing market, and it has a place on the back bar.” Sanchez insists he and Ramirez aren’t trying to replicate Mexican mezcal on Texas soil. “We’re trying to create something uniquely American.”